- Pathophysiology/Etiology

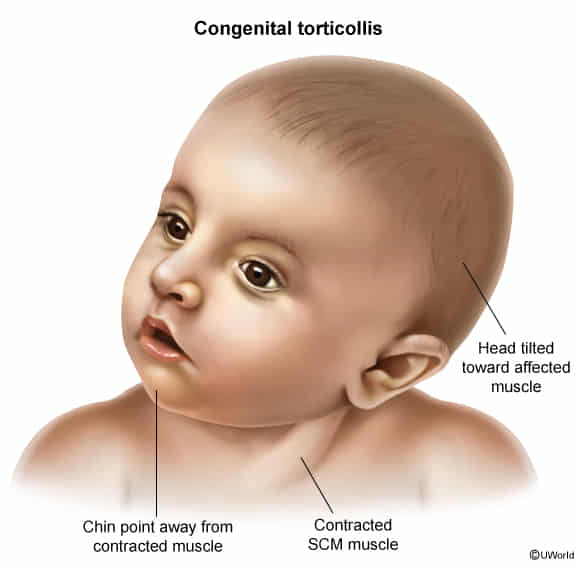

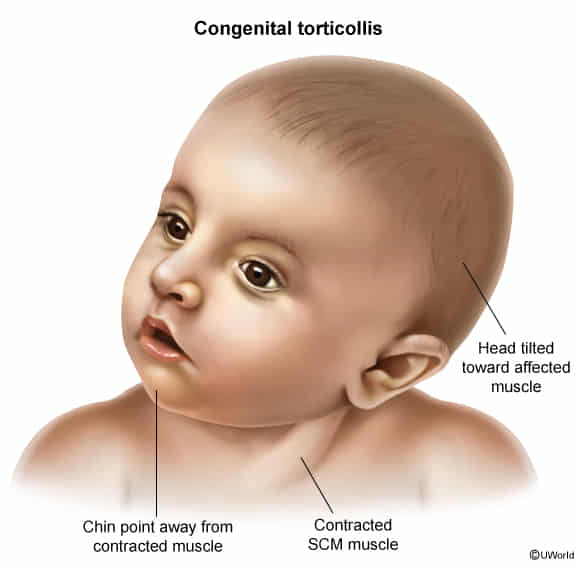

- Unilateral contracture and shortening of the sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, leading to fibrosis.

- The exact cause is often unknown, but proposed mechanisms include intrauterine malposition (e.g., crowding), birth trauma (especially breech), or perinatal compartment syndrome of the SCM.

- Also known as twisted neck or wryneck.

- Clinical Presentation

- Usually noted within the first few weeks to months of life.

- Classic posture: Head tilted (ipsilateral lateral flexion) toward the affected SCM muscle, with the chin rotated to the contralateral side.

- A firm, non-tender, palpable mass (sometimes called a “pseudotumor” or SCM mass) may be present in the belly of the SCM in up to 50% of cases; this mass typically resolves by 4-6 months.

- Limited passive and active range of motion of the neck.

- Diagnosis

- Primarily a clinical diagnosis based on physical examination of the infant’s head posture and neck range of motion.

- Ultrasound can be used to confirm SCM thickening or fibrosis and to rule out other neck masses, though it’s not always necessary.

- X-rays of the cervical spine may be indicated to rule out bony abnormalities if the presentation is atypical or fails to respond to treatment.

- Differential Diagnosis (DDx)

- Klippel-Feil syndrome: Congenital fusion of cervical vertebrae.

- Ocular torticollis: Caused by superior oblique palsy; head tilt is a compensatory maneuver to correct diplopia.

- Neurologic causes: Posterior fossa tumors, syringomyelia, or Arnold-Chiari malformation can present with abnormal head posture.

- Sandifer syndrome: Spasmodic torticollis associated with gastroesophageal reflux (GERD).

- Acquired torticollis: May result from trauma, infection (e.g., Grisel’s syndrome), or inflammation.

- Management/Treatment

- First-line treatment: Conservative management with physical therapy and a home stretching program. This includes passive stretching of the SCM and active strengthening of contralateral muscles.

- Parental education is key: Teaching parents positioning techniques (e.g., encouraging the infant to turn their head to the non-preferred side during feeding and play) and the importance of “tummy time”.

- Over 90% of cases resolve with conservative therapy, especially if started before 6 months of age.

- Botulinum toxin injections or surgical release of the SCM are reserved for refractory cases that do not respond to at least a year of conservative management.

- Key Associations/Complications

- Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH): A strong association exists (5-20% of cases), so all infants with congenital torticollis should have a thorough hip examination (e.g., Ortolani, Barlow maneuvers) and may require hip imaging.

- Plagiocephaly: Asymmetrical flattening of the skull on the contralateral side due to the infant consistently lying on that side.

- Untreated torticollis can lead to permanent craniofacial asymmetry and restricted neck motion.

- Gross motor delays may occur but often resolve with treatment.