-

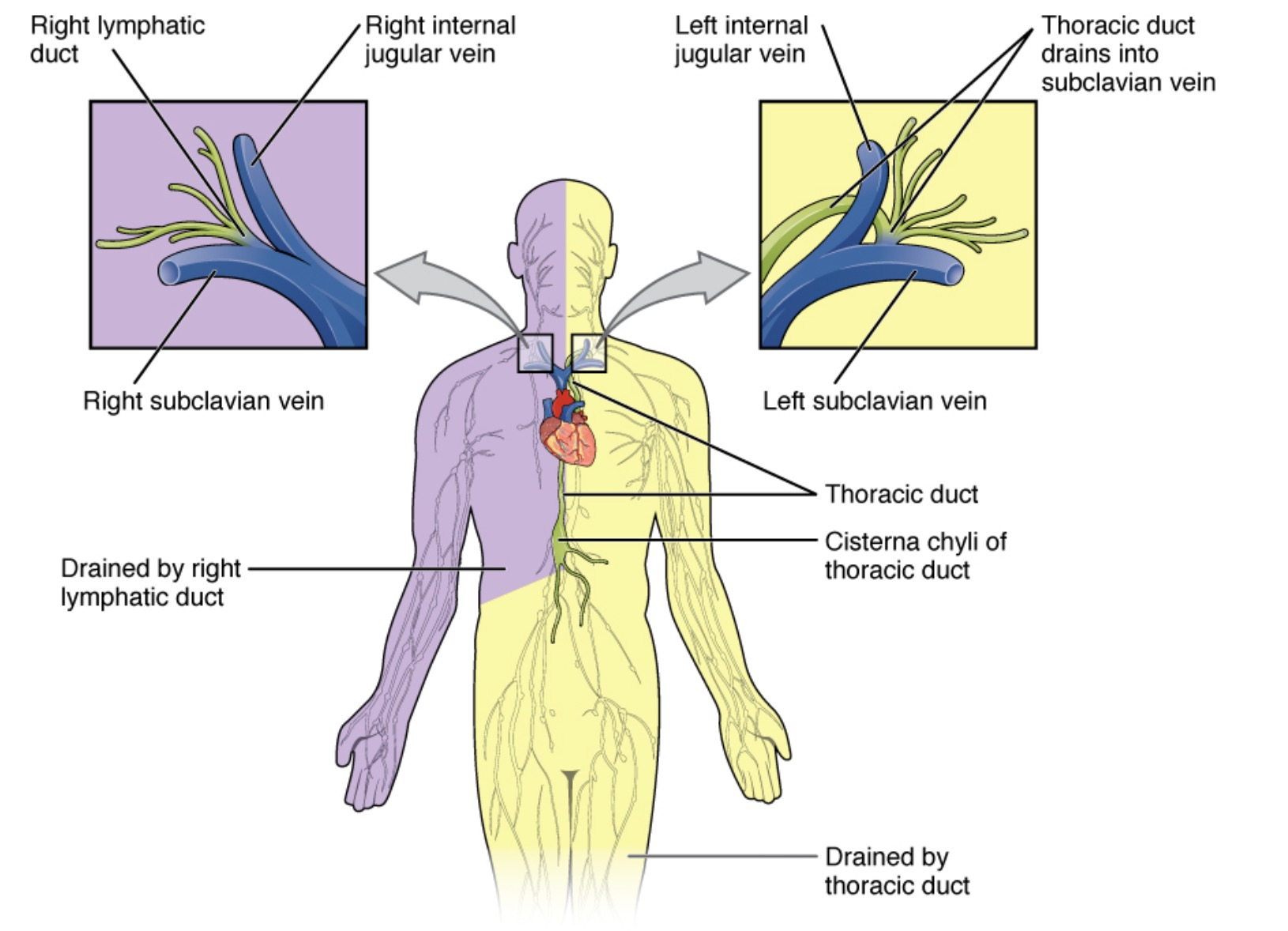

Patho/Etiology: Accumulation of chyle (lymphatic fluid from the intestines) in the pleural space due to disruption or obstruction of the thoracic duct.

- Traumatic: Most common overall cause. Often iatrogenic, secondary to thoracic surgery (e.g., esophagectomy, cardiac surgery) or chest trauma.

- Non-traumatic: Malignancy is the most frequent non-traumatic cause, especially lymphoma. Other causes include infections (e.g., TB, filariasis), sarcoidosis, cirrhosis, and superior vena cava (SVC) thrombosis.

- Traumatic: Most common overall cause. Often iatrogenic, secondary to thoracic surgery (e.g., esophagectomy, cardiac surgery) or chest trauma.

-

Clinical Presentation: Symptoms relate to the size and rate of fluid accumulation.

- Progressive dyspnea is the most common symptom.

- Cough, chest pressure.

- Fever and sharp chest pain are typically absent.

- Signs of pleural effusion on exam: decreased breath sounds, dullness to percussion.

- Post-traumatic chylothorax may present up to 10 days after the initial injury.

-

Diagnosis:

- Thoracentesis (Gold Std): Pleural fluid analysis is key.

- Appearance: Milky, opalescent fluid is classic but only seen in about half of cases; can be serous or serosanguineous, especially in fasting patients.

- Biochemistry: Definitive diagnosis relies on lipid analysis.

- Triglycerides > 110 mg/dL (diagnostic).

- Triglycerides 50-110 mg/dL is borderline; requires lipoprotein analysis to confirm chylomicrons.

- Triglycerides < 50 mg/dL makes chylothorax unlikely.

- Pleural fluid cholesterol to triglyceride ratio < 1.

- Imaging: CXR shows pleural effusion. CT chest can help identify the underlying cause (e.g., mediastinal mass, trauma). Lymphangiography (conventional or MR) can localize the leak if needed for intervention.

- Thoracentesis (Gold Std): Pleural fluid analysis is key.

-

DDx (of pleural effusion):

- Pseudochylothorax: Milky appearance but due to high cholesterol (>200 mg/dL) and cholesterol crystals, not triglycerides. Seen in chronic inflammatory effusions like TB or rheumatoid arthritis.

- Empyema: Purulent fluid, high neutrophils, positive culture. Supernatant is clear after centrifugation, unlike chylothorax.

- Hemothorax: Bloody fluid, Hct of fluid is >50% of serum Hct.

- Transudative vs. Exudative effusions: Chylothorax is typically an exudate by Light’s criteria.

-

Management/Treatment:

- Conservative (First-line): Goal is to decrease chyle flow.

- Drainage of pleural fluid (thoracentesis or chest tube) for symptom relief.

- Dietary modification: Total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or a low-fat diet with medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) supplementation (MCTs are absorbed directly into the portal system, bypassing lymphatics).

- Medical: Octreotide/Somatostatin can reduce chyle flow.

- Invasive/Surgical: Indicated for failure of conservative management, high-output fistulas (>1-1.5 L/day), or rapid nutritional decline.

- Thoracic duct ligation (standard surgical approach).

- Thoracic duct embolization (interventional radiology).

- Pleurodesis (chemical or surgical).

- Conservative (First-line): Goal is to decrease chyle flow.

-

Key Associations/Complications:

- Complications: Result from chronic loss of chyle.

- Malnutrition and weight loss (loss of fats, proteins, fat-soluble vitamins).

- Immunosuppression (loss of T-lymphocytes and immunoglobulins), leading to increased infection risk.

- Dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities.

- Associations: Lymphoma, Down syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Turner syndrome.

- Complications: Result from chronic loss of chyle.