Epidemiology

Peak incidence: neonatal period (first 30 days of life) and during puberty (10–14 years)

Etiology

- Idiopathic

- Iatrogenic

- Following a testicular procedure with incorrect positioning of testis

Pathophysiology

- Initial twisting obstructs the low-pressure venous outflow (pampiniform plexus), while high-pressure arterial inflow continues.

- Leads to venous congestion, edema, and hemorrhage.

- ↑ Intratesticular pressure eventually exceeds arterial pressure, cutting off arterial supply → ischemia and infarction of the testicle.

- Two main types:

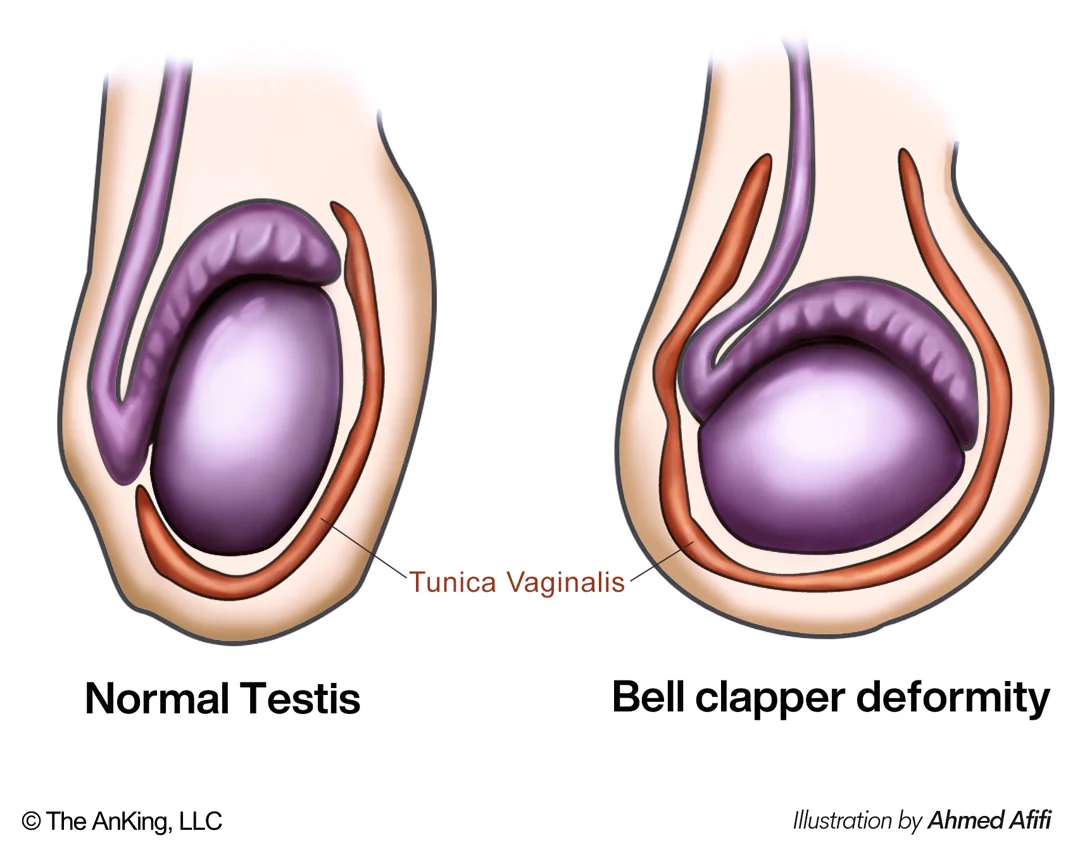

- Intravaginal torsion: Most common (>90%), seen in adolescents/young adults. Caused by an anatomical defect known as the “bell clapper” deformity, where the tunica vaginalis has an abnormally high attachment to the spermatic cord, allowing the testis to rotate freely within it.

- Extravaginal torsion: Seen in neonates. The testis, epididymis, and tunica vaginalis are not yet fixed to the scrotal wall, allowing the entire complex to tort.

Clinical features

- Abrupt onset of severe testicular pain and/or pain in the lower abdomen

- swollen and tender testis

- Nausea and vomiting

- Abnormal position of the testis

- Scrotal elevation (high-riding testis)

- Absent cremasteric reflex

- Impairment of nerves within the cord

- Negative Prehn sign

- A physical examination finding in which elevation of the scrotum relieves testicular pain. A positive Prehn sign is associated with epididymitis; a negative Prehn sign is associated with testicular torsion.

- Elevation of the scrotum can improve venous drainage and relieve edema in epididymitis; but cannot relieve ischemia in testicular torsion.

Tip

- Testicular torsion: negative Prehn sign, negative cremasteric reflex

- Epididymitis: positive Prehn sign, positive cremasteric reflex