| AGONIST WITH | POTENCY | EFFICACY | REMARKS | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

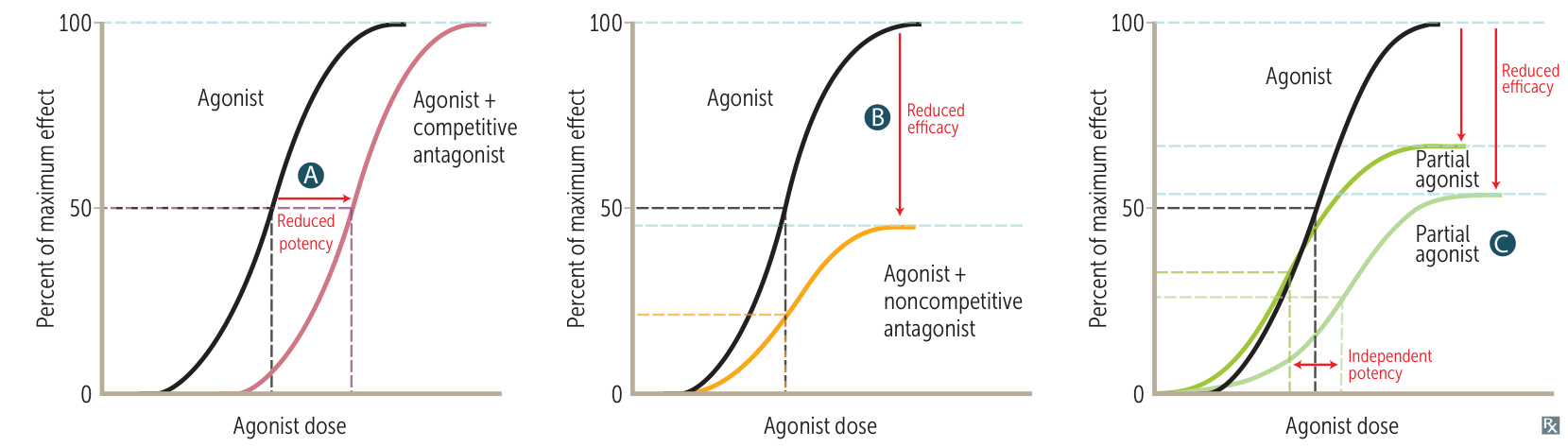

| (A) Competitive antagonist | ↓ | No change | Can be overcome by ↑ agonist concentration | Diazepam (agonist) + flumazenil (competitive antagonist) on GABAₐ receptor. |

| (B) Noncompetitive antagonist | No change | ↓ | Cannot be overcome by ↑ agonist concentration | Norepinephrine (agonist) + phenoxybenzamine (noncompetitive antagonist) on α-receptors. |

| (C) Partial agonist (alone) | Independent | ↓ | Acts at same site as full agonist | Morphine (full agonist) vs buprenorphine (partial agonist) at opioid μ-receptors. |

| Inverse agonist (alone) | Independent | Independent | Binds to a constitutively active receptor, thereby reducing its activity; has the opposite effect of an agonist | H1 antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine) |

Tip

- A partial agonist binds to and activates a receptor, but with lower efficacy (intrinsic activity) than a full agonist.

- It can never produce the maximal response, even at full receptor occupancy.

- Dual Action:

- In the absence of a full agonist: It acts as an agonist, producing a submaximal effect.

- In the presence of a full agonist: It acts as a competitive antagonist by competing for receptor binding sites. This reduces the overall effect of the full agonist, bringing the net response down to the level of the partial agonist’s own maximal effect.

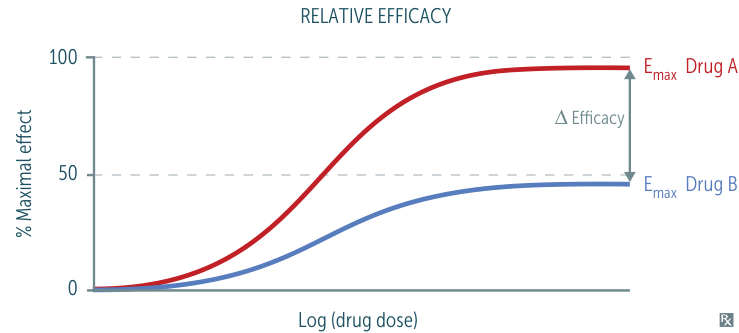

- Efficacy: The maximum effect a drug can produce, regardless of the dose. It answers the question: “How well does it work?”

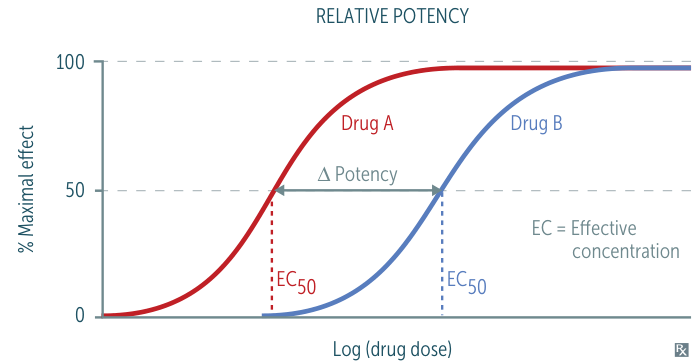

- Potency: The amount of drug needed to produce a given effect (e.g., 50% of the maximal effect, known as EC50). It answers the question: “How much is needed?”